In the following case study, I explore in depth the issue of learning the geological time scale — names, dates, and defining events. The emphasis is on developing mnemonics, of course, but an important part of the discussion concerns when and when not to use mnemonics, and how to decide.

The Geological Time Scale

Phanerozoic Eon 542 mya—present

Cenozoic Era 65 mya—present

Neogene Period 23 mya—present

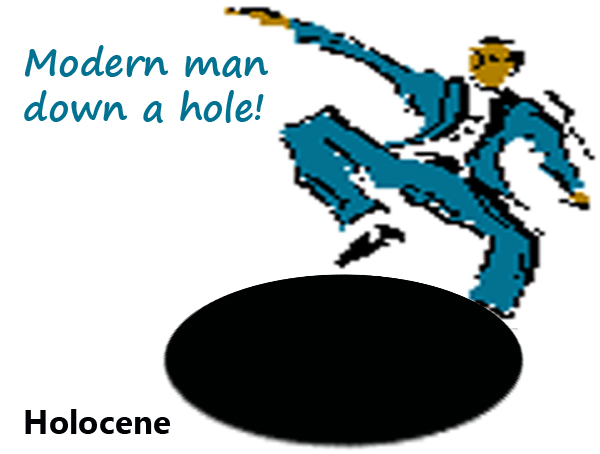

Holocene Epoch 8000 ya—present

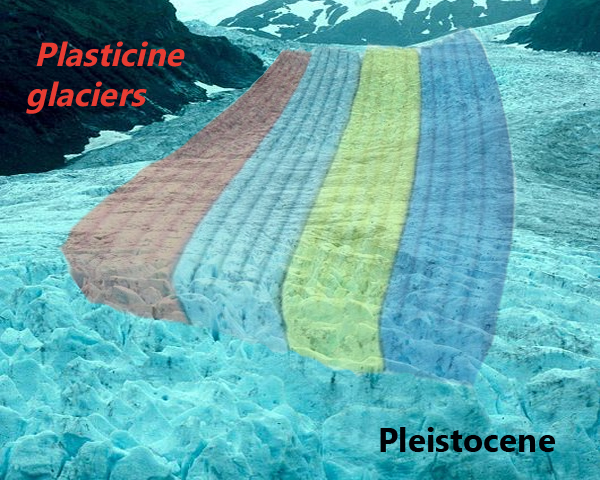

Pleistocene Epoch 1.8 mya—8000ya

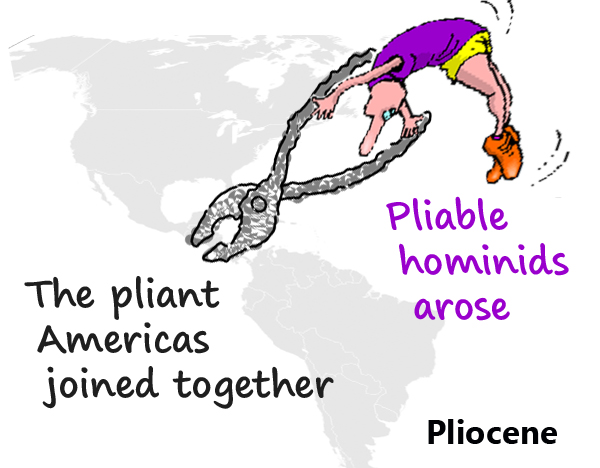

Pliocene Epoch 5.3 mya—1.8 mya

Miocene Epoch 23 mya—5.3 mya

Paleogene Period 65 mya—23 mya

Oligocene Epoch 34 mya—23 mya

Eocene Epoch 56 mya—34 mya

Paleocene Epoch 65 mya—56 mya

Mesozoic Era 250 mya—65 mya

Cretaceous Period 145 mya—65 mya

Jurassic Period 200 mya—145 mya

Triassic Period 250 mya—200 mya

Paleozoic Era 542 mya—250 mya

Permian Period 300 mya—250 mya

Carboniferous Period 360 mya—300 mya

Devonian Period 416mya—360 mya

Silurian Period 444 mya—416 mya

Ordovician Period 488 mya—444 mya

Cambrian Period 542mya—488 mya

Precambrian 4560 mya—542 mya

Proterozoic Eon 2500 mya—542 mya

Archean Eon 3800 mya—2500 mya

Hadean Eon 4560 mya—3800 mya

How do we set about learning all this? Let’s look at our possible strategies.

Memorizing new words, lists and dates

Acronyms

A common trick to help remember the geological time scale is to use a first-letter acronym, such as the classic:

Camels Often Sit Down Carefully; Perhaps Their Joints Creak? Persistent Early Oiling Might Prevent Permanent Rheumatism.

(This begins with the Cambrian Period and moves forward in time; note that in this traditional mnemonic the Holocene Epoch is here thought of by its older name of “Recent Epoch”.)

What’s the problem with this, as a way of remembering the geological scale?

It assumes we already know the names.

The principal (and often, only) purpose of an acronym is to remind you of the order of items that you already know.

A common problem with acronyms (first-letter by definition) is that there are often repeats of initials, causing confusion. A more useful strategy (though far more difficult) might be to use the first two or preferably three letters of the words. This not only distinguishes more clearly between items, but also provides a much better cue for items that are not hugely familiar. For example, here’s one I came up with for the geological time-scale:

Hollow Pleadings Plight Miosis;

Olive Eons Pall Creation; (or Olive Eons Palm Credulous, for a slight rhyme)

Juries Trick Perplexed Carousers;

Devils Silence Ordered Campers.

Because it is extremely difficult to make a meaningful sentence with these restraints (largely because of rare combinations such as Eo- and Mio- and to a lesser extent, Pli, Oli, and Jur), I have used rhythm to group it into a verse. There’s a slight rhyme, but it’s amazing how much power rhythm has to facilitate memory on its own.

It is easier, of course, to construct a sentence with these items if you are allowed to include a few “insignificant” words (i.e., not nouns or verbs) to hold them all together. Here’s a possible sentence, this time starting from the oldest and moving forward to the most recent:

Campers Order Silver Devils to Carry Persons Tricking Jurisprudent Cretins in Palmy Eons of Olive Milk and Pliant Pleadings for Holidays

The problem with both this and the “verse” is that they are too long, given their difficulty, to be readily memorable. The answer to this is organization, and later we’ll discuss how to use organization to reduce the mnemonic burden. But first, let’s deal with another problem.

Although the use of three-letter acronyms lessens the need for such deep familiarity with the items to be learned, you do still need to know the items. With names as strange as the ones used in the geological time-scale, the best strategy is probably the keyword mnemonic (or at least a simplified version).

Looking for meaning

But let’s start by considering the origin of the names. If they’re meaningful, if there is a logic to the naming that we can follow, our task will be made incomparably easier.

Unfortunately, in this case there’s not a lot of logic to the naming. Some of the periods are named after geographical areas where rocks from this period are common, or where they were first found — these are probably the easiest to learn. The epochs in particular, however, are problematic, as they are very similar, being based on ancient Greek (in which few students are now trained), and, most importantly of all, being essentially meaningless.

Let’s look at them in detail. The common cene ending comes from the Greek for new (ceno).

- Holocene is from holos meaning entire

- Pleistocene is from pleistos meaning most

- Pliocene is from pleion meaning more

- Miocene is from meion meaning less

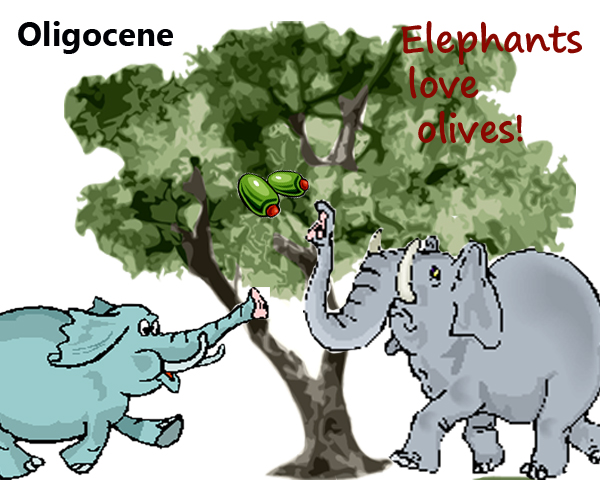

- Oligocene is from oligos meaning little, few

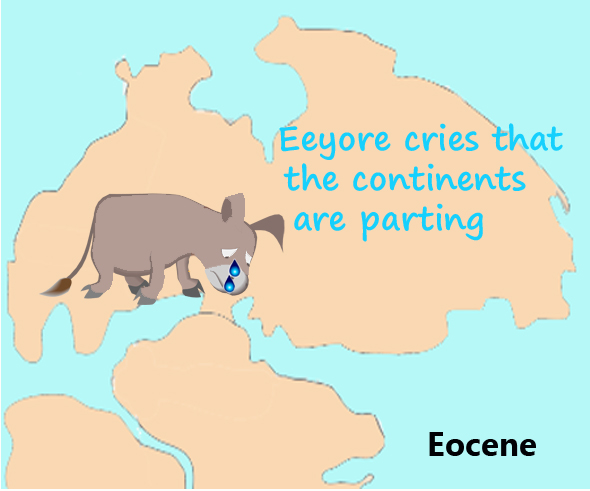

- Eocene is from eos meaning dawn

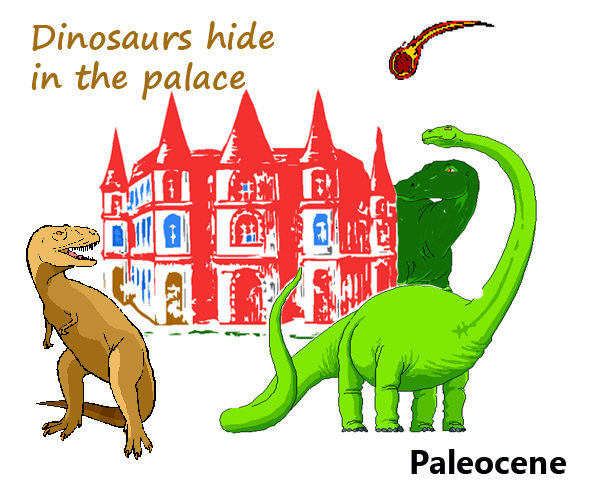

- Paleocene is from palaois meaning old

So we have

- Holocene: entire new

- Pleistocene: most new

- Pliocene: more new

- Miocene: less new

- Oligocene: little new

- Eocene: dawn new

- Paleocene: old new

You could find this helpful (remember that we’re moving backward in time, so that the Holocene is indeed the newest of these, and the Paleocene is the oldest), but the naming is really too arbitrary and meaningless to be of great help.

Better to come up with associations that have more meaning, even if that meaning is imposed by you. Here’s some words you could use:

- Holocene: holy; hollow; hologram; holly

- Pleistocene: plasticine; plastic

- Pliocene: pliable; pliant; pliers

- Miocene: my; milo; myopic

- Oligocene: oligarchy; olive; oliphaunt (! Notice that the words don’t have to be familiar to the whole world, even the dictionary-makers; the important thing is that they have significance to you)

- Eocene: eon; enzyme; obscene (note that it is not necessary for the word to begin with the same letter(s) — a particularly difficult task in this instance; what’s important is whether the word will serve as a good link for you)

- Paleocene: palace; palatial; paleolithic

To tie your chosen word to the word to be learned, you must form an association (that’s why it’s so important to choose a word that’s good for you — associations are very personal). For example, you could say:

- Holograms are very recent (the Holocene is the most recent epoch)

- Glaciers are plastic or My glaciers are made of plasticine (the Pleistocene was the time of the “Great Ice Age”)

- The pliant Americas joined together or Pliable hominids arose (Hominidae began in the Pliocene, and North and South America joined up)

- Mild weather saw Africa collide with Asia (the Miocene was warmer than the preceding epoch; during this time Africa finally connected to Eurasia)

- Elephants become oligarchs! (during the Oligocene mammals became the dominant vertebrates)

- Continents obscenely separate (Laurasia, the northern supercontinent, began to break up at the beginning of the Eocene; Gondwanaland, the southern supercontinent, continued its breakup)

- Pale from the disaster, we pull ourselves together (the Paleocene marks the beginning of a new era, after the K-T boundary event (thought by many to be an asteroid impact) in which the dinosaurs and so much other life died)

Now this is not, of course, in strict accordance with the keyword method. According to this method, we should choose a word as phonetically similar to the word-to-be-learned as possible, and as concrete as possible, and then form a visual image connecting the two. While this is fine with learning a different language (the most common use for the keyword method, and the one for which it was originally designed), it is clearly very difficult to create an image for something as abstract and difficult to visualize as a period of time.

It’s also often difficult to find keywords that are both phonetically similar and concrete. We must improvise as best we may. What you need to bear in mind is that you are searching for an association that will stick in your mind, and link the unfamiliar (the information you are learning) to the familiar (information already well established in your mind).

With this in mind, look again at the suggested associations. This time, think in terms of whether you can make a picture in your mind.

Instead of “Holograms are very recent”, you might want to form an image of someone falling into a hole (tying the Holocene to the “Age of Humans”).

Instead of “Holograms are very recent”, you might want to form an image of someone falling into a hole (tying the Holocene to the “Age of Humans”).

Glaciers made of plasticine might stand.

If you can visualize very limber (perhaps in distorted postures) ape-like humans, Pliable hominids might be satisfactory, or you may need to fall back on the pliers — perhaps an image of pliers bringing North and South America together.

If you can visualize very limber (perhaps in distorted postures) ape-like humans, Pliable hominids might be satisfactory, or you may need to fall back on the pliers — perhaps an image of pliers bringing North and South America together.

Mild weather isn’t terribly imageable; you might like to imagine milk pouring from the joint where Africa and Eurasia have collided.

Mild weather isn’t terribly imageable; you might like to imagine milk pouring from the joint where Africa and Eurasia have collided.

Oligarchs is likewise difficult, but you could visualize elephants under olive trees, eating the olives.

Oligarchs is likewise difficult, but you could visualize elephants under olive trees, eating the olives.

And now of course, we come to the most difficult — the Eocene. Here’s a thought, for those brought up with Winnie the Pooh. If you have a clear picture of Eeyore, you could use him in this image. Perhaps Eeyore is standing on one part of the separating Laurasia (looking appropriately disconsolate).

And now of course, we come to the most difficult — the Eocene. Here’s a thought, for those brought up with Winnie the Pooh. If you have a clear picture of Eeyore, you could use him in this image. Perhaps Eeyore is standing on one part of the separating Laurasia (looking appropriately disconsolate).

The Paleocene might best be associated with a palace, if we’re looking for something imageable — perhaps dinosaurs sheltering in a palace as the asteroid comes down and destroys it.

You see from this that the demands of visual associations are often quite different from those of verbal associations. Both are effective. Whether you use verbal or visual associations should depend not only on your personal preference (some people find one easier, and some the other), but also on what the material best affords — that is, what is easiest, what comes more readily to mind, and also, which association will be less easily forgotten.

But mnemonics only take you so far. While very useful for learning new words, and for learning lists, they are not a good basis for developing an understanding of a subject — and unlike the situation of learning a language, a scientific topic definitely requires a more holistic approach. Mnemonics here are very much an adjunct strategy, not a complete solution. So before using mnemonics to fix specific hard-to-remember details in my brain, I would begin by organizing the information to be learned, with the goal of cutting it into meaningful chunks.

Excerpted from Mnemonics for Study