In my article on using cognates to help you learn vocabulary in another language, I gave the example of trying to learn the German word for important, ‘wichtig’, and how there’s no hook there to help you remember it (which is why so many of us fall back on rote repetition to try to hammer vocabulary into our heads). However, I pointed out, if you knew that wichtig descends from a root that also produced weigh, weight, and weighty, you could reframe the translation as wichtig = weighty, important, and now you have your meaningful connection.

Such connections don’t do away entirely with the need to practice, but they do mean that much less practice is required. You just have to focus on that meaningful connection.

Let’s have a look at that in action.

A list of the 1,000 most commonly spoken Italian words, generated from subtitles of movies and television series, includes 475 nouns plus 17 numbers (cardinal and ordinal, so I’ve put them in a separate category).

I have classified all 475 nouns into groups based on the available meaningful connections for an English speaker learning Italian:

-

208 are very easy, meaning they’re very close to their English counterparts (Group 1)

-

54 are still fairly easy, being cognate with their English counterparts, and similar enough if you’re looking for it (Group 2)

-

101 are harder to see, but are still cognate (Group 3)

-

77 are still cognate, but more difficult (Group 4)

-

23 have cognates, but with obscure words or common French or Spanish words, or the similarity is much less evident (Group 5)

-

12, and only 12, are unrelated, and thus require a mnemonic connection (Group 6)

Of the 17 numbers, all are cognate, and most of them quite obviously so.

In other words, about 94% of this group have some meaningful connection with an English word. I will agree that the nouns and numbers are far more likely to be cognate than other parts of speech, but still, this is impressive.

I am working on a workbook that will expand on these, and contain all the top 1000 words. In the meantime, I hope the following lists of these nouns and numbers are useful.

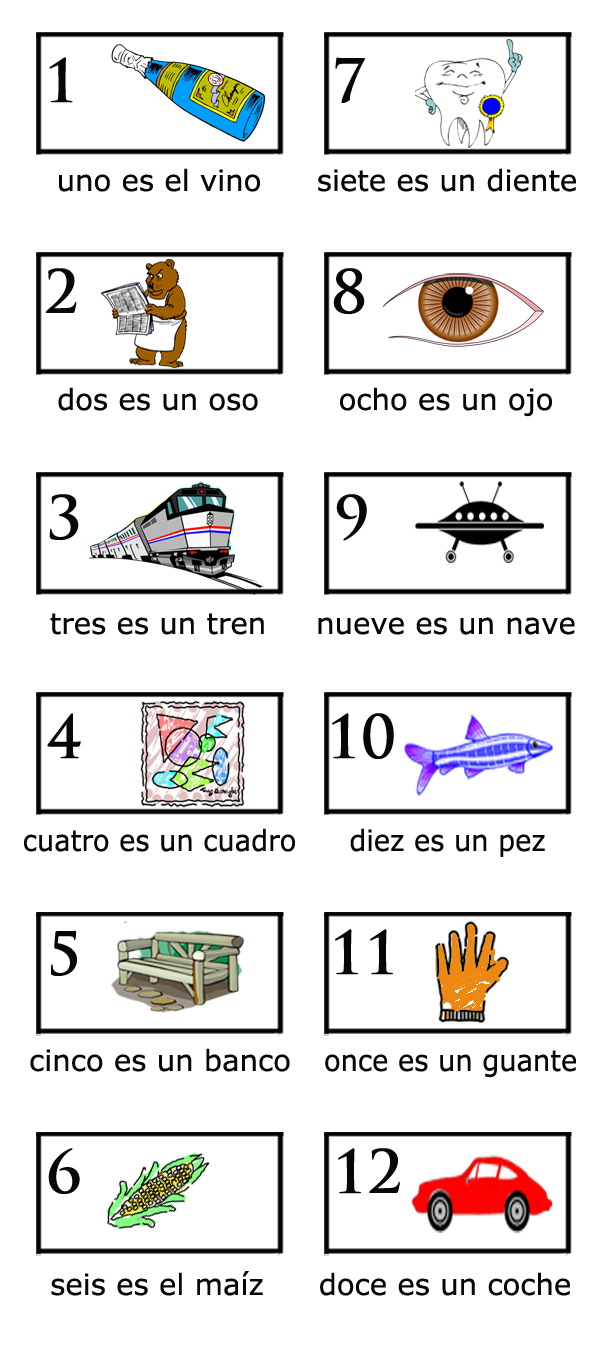

Here are the numbers that appear in the list:

uno, one

due, two — think duo, dual

tre, three — also cognate with tri-, as in triangle, trio, tripod

quattro, four — think of quadruple, quadrilateral, quadruped, square

cinque, five — cognate with five, but this is not very obvious; also cognate with quinquennial and quinate, and of course French cinq

sei, six — cognate, but you do have to focus on the first part of ‘six’!

sette, seven — cognate but it may help to think of September (which used to the 7th month, before the Romans reformed the calendar by popping in what would become July and August), also septenarian and septuagenarian; also French sept

otto, eight — think octagon, octopus, octave

nove, nine — French neuf, English November (same reason: it started off as the 9th month), novena

dieci, ten — cognate with decimal, and French dix

venti, twenty — okay, there are words in English cognate with this, but they’re pretty rare; still, if you drop the initial t, the words become much more similar

cento, hundred — cognate with cent, century

migliaia, thousand — think of millimeter, millisecond, etc

milione, million

primo, first — think of primary

secondo, second

terzo, third

Ok, let’s look at the nouns. First, the ones that are very similar to their English counterparts:

Group 1

abilità, skill, ability

accordo, accord, agreement, chord (mus.)

animale, animal

appartamento, apartment, flat

area, area

arte, art

atomo, atom

atto, act

auto, car (automobile)

banca, bank

banda, band

bar, bar

base, base

bit, bit

blocco, block

bordo, edge, border

campo, field, camp

capitale, capital

capitano, captain

carattere, character

caso, case

causa, cause

cella, cell

cent, cent

centro, center

città, city, town

classe, class

colonia, colony

colonna, column

colore, color

commercio, trade, commerce

condizione, condition

consonante, consonant

continente, continent

controllo, control

copia, copy

corda, rope, cord

corrente, current

corso, course

costa, coast

costo, cost

cotone, cotton

cuoco, cook

cura, care, treatment, cure

danza, dance

decimale, decimal

deserto, desert

difficoltà, trouble, difficulty

discussioni, discussion, argument

divisione, division

dizionario, dictionary

dollaro, dollar

effetto, effect

elemento, element

energia, energy

esempio, example

esercizio, exercise

esperienza, experience

esperimento, experiment

est, east

evento, event

famiglia, family

fatto, fact

feltro, felt

fico, fig

fiera, fair, exhibition

figura, figure

finale, final

finitura, finish

foresta, forest

forma, form, shape

forza, force, strength

frase, sentence, phrase

frazione, fraction

frutta, fruit

gas, gas

gatto, cat

giardino, garden

gruppo, group

idea, idea

industria, industry

insetto, insect

interesse, interest

lettera, letter

liquido, liquid

linea, line

livello, level

log, log

lotto, lot

macchina, machine

magnete, magnet

mais, maize, corn

mappa, map

marchio, mark

massa, mass

materia, matter

materiale, material

melodia, melody

messaggio, message

modello, model, pattern

motivo, reason, motive

metallo, metal

metodo, method

minuto, minute

molecola, molecule

momento, moment

montagna, mountain

monte, mount, mountain

moto, motion

motore, engine, motor

musica, music

natura, nature

nazione, nation

nome, name

nord, north

nota, note

numerale, numeral

numero, number

oceano, ocean

offerta, offer

oggetto, object

olio, oil

ora, hour

ordine, order

organo, organ

pagina, page

palla, ball

papà, dad

paragrafo, paragraph

parte, part

partito, party

pausa, pause, break

periodo, period

persona, person

persone, people

pistola, gun

porto, port

posa, pose

posizione, position

possibilità, possibility, chance

pratica, practice

presente, present

problema, problem

processo, process

prodotto, product

proprietà, property

punto, point

quarto di gallone, quart

quota, share, portion, quota

quoziente, quotient

radio, radio

record, record

regione, region

resto, rest

risultato, result

rock, rock

rosa, rose

sale, salt

scala, scale

scienza, science

scuola, school

segmento, segment

segno, sign — also signal

senso, sense

sistema, system

sezione, section

sillaba, syllable

simbolo, symbol

soluzione, solution

sorpresa, surprise

sostanza, substance

spazio, space

stato, state

stazione, station

storia, story, history

strada, street, road

stringa, string

strumento, instrument, tool

studente, student

studio, study

successo, success

sud, south

suffisso, suffix

supporto, support

tavolo, table

team, team

temperatura, temperature

termine, term

test, test

tipo, type

tono, tone

totale, total

treno, train

triangolo, triangle

tubo, tube

turno, turn

ufficio, office

umano, human

unità, unit, unity

uso, use

valle, valley

valore, value

vapore, steam, vapor / vapour

velocità, speed, velocity

verbo, verb

vigore, force, vigor / vigour

villaggio, village

visita, visit

vittoria, win, victory

Group 2

the fairly easy nouns (but you may have to work a little to see the connection)

acqua, water — aqua, aquatic

amico, friend — amicable, Spanish amigo

angolo, corner — angle

anno, year — annual

amore, love — amorous, French amour

bambino, child, baby

barca, boat — barge, barque

bellezza, beauty — belle (the belle of the ball)

bevanda, drink — beverage

cane, dog — canine

carne, meat — carnivore

casa, home, house — well-known in English from the Spanish casa; also cognate with French chez (to, at), as in chez moi (at my house)

cavallo, horse — cavalry

cielo, sky — ceiling

collo, neck — collar

corpo, body — corpse

cravatta, tie — cravat

denti, teeth — dental, dentist

dimensione, size — dimension

discorso, speech, discourse

donna, woman — madonna, dame

erba, grass — herb

fine, end — final, also French fin

fratello, brother — fraternal, fraternity

libro, book — library

lingua, language — cognates, also linguistics, lingo

luna, moon — lunar

madre, mother — cognates, also maternal, maternity

mano, hand — manuscript (written by hand), also French main, Spanish mano

mare, sea — marine, maritime

mente, mind — cognates, also mental

meraviglia, wonder — marvel, marvellous

mercato, market — cognates, also merchant, mercantile

morte, death — mortal, mortality

naso, nose — cognates, also nasal

nave, ship — nautical, navy, navigate

pneumatico, tyre / tire — pneumatic tyre

poesia, poem — also poetry, poetic

posto, place, spot — post, position

potenza, power — potent

regola, rule — cognates, also regulate, regular

risposta, answer — response, riposte

salto, jump — saltatory, saltation, also French sauter

sangue, blood — sanguinary, sanguine, exsanguinate, also French sang, Spanish sangre

signora, lady — cognate with senior, sire

sole, sun — solar

stella, star — stellar

terra, land, earth, ground — terrestrial, also French terre

tratto, stretch (of road, river, land) — tract

uomo, man — human

vento, wind — cognates, also ventilate

vista, view, sight — vista

vita, life — vital

Group 3

Here are the words that are cognate, but less obviously so:

alimentazione, supply, feed, diet — alimentary (canal), alimentation

anello, ring — annulus, annular.

aria, air — aura, air, aerate, aerial

avviso, notice, advice, advertisement

calore, heat — calorie, calorific

campana, bell — is in fact the word for a church bell in English, but this is not a well-known word! also cognate with campanology, the study of bells

canzone, song — chant, French chanson

capelli, hair — capillary (because capillary veins are as fine as hair)

capo, chief — capo (come into English through the portrayals of the mafia), capital, per capita

cappello, hat — cap

coda, tail — coda, caudal, caudate.

copertura, cover — cover, covert

desiderio, wish — desire

dito, finger — digit

divertimento, fun — diversion

fattoria, farm — factor (meaning someone who acts as a business agent, especially a manager of a landed estate)

ferro, iron — ferric, meaning related to iron; also French fer

ferrovia, railway — ‘iron way’, A railway is an iron way, ferric via

fila, row — file (in the sense of people in a row, moving ‘in file’)

finestra, window — defenestrate, also French fenêtre, Spanish fenestra, German Fenster

fiore, flower — floral, flower; also Spanish flor, French fleur

flusso, flow — cognate with flux (when something’s in flux, it’s still in flow)

foglio, sheet, leaf — folio, foliate, exfoliate

fondo, bottom — fundamental, profound.

genitore, parent — progenitor, genitive

gioia, joy

giorno, day — journal, also French jour, journée

grado, degree, level, grade — grade, gradient

grafico, chart — graph, graphic

guerra, war — guerilla, also French guerre

immagine, picture — image, imagine

impianto, plant — implant, plant

isola, island — isle, isolated

lago, lake — lagoon

lato, side — lateral (relating to the side), quadrilateral (four-sided)

latte, milk — latte (milky coffee), lactose, lactating

lavaggio, wash — lave, lavatory, launder

lavoro, work, job — labour/labor

libbra, pound — this is why the abbreviation for pound is lb. (from Latin libra), also French livre, Spanish libra, and the zodiac sign Libra

luce, light — lux, lucent, translucent

lunghezza, length — from lungo, meaning long

maschi, men — macho, masculine

mattina, morning — matins (an early morning church service), also French matin

medico, doctor — medic, medical

mese, month — cognate with menses, trimester (3 months), semester (six months); also Spanish mes and French mois

mezzogiorno, noon — break it down into mezzo-giorno = mid-day

miglio, mile — cognates, and related to migliaia, thousand, from the Roman mile being 1000 paces

miniera, mine — cognates

modo, manner, way — mode

mondo, world — mundane (worldly, belonging to the world), also French monde, Spanish mundo

muro, wall — mural, immured

nascita, birth — nascent, renaissance

negozio, store, shop — negotiate

nemico, enemy — inimical, enemy

notte, night — nocturnal, and indeed night

nube, cloud — nebula, nebulous

onda, wave — undulate

oro, gold — auric, French or

orologio, watch, clock — horology

ossigeno, oxygen — cognates

osso, bone — ossify

ovest, west — cognates, also French ouest, Spanish oeste

padre, father — padre, pater, paternal, paternity

pane, bread — French pain, as in pain au chocolat; also Spanish pan

passo, step — pace

pensiero, thought — pensive, also French penser

pensione, board — pension

pesce, fish — Pisces, piscatory, also Spanish pez, and French poisson

pezzo, piece — cognates (also, you can think of a piece of pizza!)

pianeta, planet — cognates

piano, plane, plan, floor — cognates

piazza, square, plaza — plaza

piede, foot — pedal, pedestrian, also French pied, Spanish pie

piedi, feet — as before

pista, track — French piste, as in the English expression "off piste"

porta, door — portal, also French porte

primavera, spring — prima is cognate with primary (1st) and vera with vernal (relating to spring)

prossimo, neighbor — proximal, proximate

radice, root — radish

re, king — rex

riva, shore — river

rotolo, roll — rotate, roll

ruota, wheel — rotate, rota

sedia, chair — sedan chair, sedentary

sedile, seat — ditto

seme, seed — semen

soggetto, subject — cognates

soldato, soldier — cognates

soldi, money — solid, an old coin called the solidus, also French sol, sou

sorella, sister — sorority, also French sœur, Spanish sor

speranza, hope — esperance, desperate (out of hope), also Spanish esperanza, French espérer

spettacolo, show — spectacle

suolo, soil — cognate with French sol, Spanish suelo

suono, sound — cognates, also French son, Spanish son, sueno

superficie, surface — superficial

uovo, egg — ovary, also French œuf, Spanish huevo

viaggio, trip — voyage

vocale, vowel — vocal (because vowels are voiced by the vocal cords with little restriction on them, in an open way)

voce, voice — cognates

volontà, will — voluntary

zucchero, sugar — cognates

Group 4

harder cognates, where the links are more obscure:

acciaio, steel — the common root means sharp; cognate with acid, acerbic, acrimony

ala, wing — cognate with alar, agile, axle

albero, tree — cognate with arbor, arboreal, arboretum, also French arbre

azienda, company — cognate with hacienda

bastone, stick — cognate with bâton

caccia, hunt — cognate with catch

camera, room — used in the expression in camera, and cognate with bicameral, chamber, cabaret

camion, truck — comes from French camion, which has passed the word into many languages, including English; may derive from chemin, meaning way, path (see Spanish camino)

cappotto, coat — cognate with cape

carica, charge (as in attack), load — cognates, also car, chariot (think of a chariot charge and a car's load)

carta, paper — cognate with card, chart

cerchio, circle — cognates, also circus

chiamata, call — cognate with claim, declaim, proclaim

chiave, key — cognate with clavis, clavichord, clavicle, clef

collina, hill — cognates, also column, colliculus (anatomical term)

colpo, blow — cognate with the English/French word coup (coup de foudre, coup d'état, coup de grâce)

coppia, pair — cognate with couple; could also think of copied

cosa, thing — cognate with cause, also French chose

cuore, heart — cognate with core, accord, also French cœur

domanda, question, request, demand — cognate with demand

estate, summer — cognate with estivate/aestivate, estival/aestival, also French été

età, age — cognate with eternal, eon

figlio, son — cognate with filial, also French fils

filo, wire — cognate with filament, file

fiume, river — cognate with fluvial, flume, fluent, fluid

folla, crowd — cognate with full, folk, also French foule

fornitura, supply — cognate with furniture, furnish

foro, hole — cognate with door, forum, forensic

fretta, hurry — cognate with Fr frit, meaning fried (as in pommes frites), and indeed English fry, fried

fuoco, fire — cognate with focus (think of the hearth historically being the focus of the home or room)

gamba, leg — cognate with gambol, and French jambe

gamma, range — cognate with gamut, and of course the Greek letter gamma (but this doesn't point to the meaning in the same way)

ghiaccio, ice — cognate with glacier, and French glace (ice, ice cream)

gioco, game — cognate with joke, juggle, also French jeu, Spanish juego

giro, ride, tour, turn — cognate with gyrate

grido, cry — may be cognate with cry, also Spanish gritar

inverno, winter — cognate with hibernate, also French hiver

lattina, can, tin (diminutive of latta, meaning the same thing) — cognate with lath, lattice (all to do with being thin, narrow)

legge, law — cognate with legal

legno, wood — cognate with ligneous, lignite

letto, bed — cognate with litter (think of the litter used for carrying the sick or wounded, not trash), also French lit

lotta, fight, struggle — cognate with lock, locket, through a root meaning to bend, twist; also French lutte, Spanish lucha

mela, apple — cognate with melon

metà, half — cognate with median, mediate

moglie, wife — cognate with moll, mollify, Molly

neve, snow — cognate with Nevada, névé, nival, and indeed snow; also French neige, Spanish nieve

occhio, eye — cognate with ocular, oculist, monocle, and indeed eye; also Spanish ojo

orecchio, ear — cognate with aural, auricular, ear, also French oreille

paese, country — cognate with peace, also French pays, Spanish país

parola, word — cognate with palaver, parole, parlay, parable, also Spanish palabra

paura, fear — cognate with French peur (also quite similar to fear)

pece, pitch — cognates

pelle, skin — cognate with pelt, pellagra, film

pericolo, danger, peril

peso, weight — cognate with suspend, pound, expense, pensive

piega, crease, fold, pleat — cognate with pleat, replica, duplicate

pietra, stone — cognate with petrify (literally, turn to stone), also French pierre, Spanish piedra

pulcino, chick — cognate with pullet, also French poulet, poule

punteggio, score — may be cognate with point (as in score a point)

rabbia, anger, rabies — cognate with rabies, rage

raccolto, crop — cognate with recollect, collect

raggio, radius, spoke — cognate with radius

ramo, branch — cognate with root, ramus, ramification (branching)

ricerca, search, research — cognates, also French chercher (Cherchez la femme!)

richiesta, claim, request, demand — cognate with require, request

rumore, noise — cognate with rumour

schiavo, slave — cognates

secolo, century — secular (from the Latin saeculum meaning generation, century, and also worldly), also French siècle, Spanish siglo

sega, saw — cognate with saw, dissect, secant, segment (notice the cutting theme)

sonno, sleep — cognate with somnolent

sostantivo, noun — cognate with substantive, with core of word (stant) cognate with stand; think of a noun as a substantive thing that stands, that is, a concrete object

spalla, shoulder — cognate with spatula, spatulate (think of the broad, flat nature of the shoulder blade), epaulettes, also Spanish espalda

tempo, weather — cognate with tempo, tempest, also French temps, Spanish tiempo

vece, stead, place (as in, in my place, in my stead) — cognate with vice versa, vice (meaning in place of, subordinate to), also week, vicissitude, vicar

vela, sail — cognate with veil, velum (a thin membrane like a veil)

vestito, dress — cognate with vestiment, vest, divest

vetro, glass — cognate with vitreous, vitrify, also French verre, vitre, and Spanish vidrio

Group 5

Those with with the hardest connections:

anatra, duck — cognate with an obscure English word, anatine, also German Ente

bisogno, need — cognate with French besoin; a possible keyword for those unfamiliar with this word is bison

bocca, mouth — another obscure cognate: buccal (relating to the cheek), also French bouche (as in Fermez la bouche!)

braccio, arm, branch — cognate with brachial; not cognate with branch, but similarity useful

bugia, lie — cognate with boast

cambiamento, a change, shift, turn — cognate with change, although not very obvious; perhaps clearer if you know that cambiamento derives from cambiare, to change, and the English comes from French changier

guscio, shell — may be cognate with cyst

pioggia, rain — cognate with pluvial, flood, float, also French pluie

pipistrello, bat — used to be vipistrello, which makes the link to cognates vespers (evening prayers) and western (where the sun sets) more obvious

pollice, inch, thumb — cognate with obscure word pollical (of the thumb), also French pouce (thumb, inch)

ruscello, stream — cognate with rivulet, also French ruisseau (but may be easier to go with a keyword: the rushing stream)

sabbia, sand — cognates from a root meaning to pour, also French sable

salita, climb — cognate with saltatory, saltation, also French sauter

scarpa, shoe — cognate with sharp, derives from Gothic word meaning sharp object with pointed ends, because shoes had a pointed end?

sentiero, path — cognate with French sentier, Spanish sendero; apparently not cognate with send, sent, but PIE root word *sent- meant to go, to travel, so could be considered so

sera, evening — here's an obscure cognate that some might know: serotine (a bat); more familiarly probably: French soir (as in bonsoir), and Spanish sera

settimana, week — cognate with September, through the sept=7 connection; also French semaine, Spanish semana

slittamento, slip, sliding — not cognate, but similarity sufficient for imagining so

sorriso, smile — cognate with risible (laughable) and riant (laughing); sorriso derives from Latin sub-rideo (below a laugh, as it were); also cognate with French sourire, souriant

stagione, season — cognate with station, also Spanish estación

taglio, cut — cognate with tagliatelle, intaglio

testa, head — cognate with French tête, Spanish testa

uccello, bird — cognate with avian, aviary, also French oiseau

Group 6

Those with no connections. These are the ones for which a mnemonic link is recommended, and I’ve provided some suggestions:

cantiere, shipyard, building site — canter into the yard

cibo, food — chip (actually cognate with ciborium, a receptacle for communion wafers, if you happen to know it; also Spanish cebo)

elenco, list — elect to the list

gara, race — cheer the race

mucca, cow — moo cow

partita, (sports) match, game — participate in the game (actually cognate with a musical term in English, if you happen to know it)

ragazza, girl / ragazzo, boy — ragged urchin

scatola, box — casket

scheda, card — the schedule is written on the card

se stesso, self — stetson

tuta, suit (sweatsuit, tracksuit, overalls) — tutu

volto, face — think of the expression volte face

Instead of “Holograms are very recent”, you might want to form an image of someone falling into a hole (tying the Holocene to the “Age of Humans”).

Instead of “Holograms are very recent”, you might want to form an image of someone falling into a hole (tying the Holocene to the “Age of Humans”).

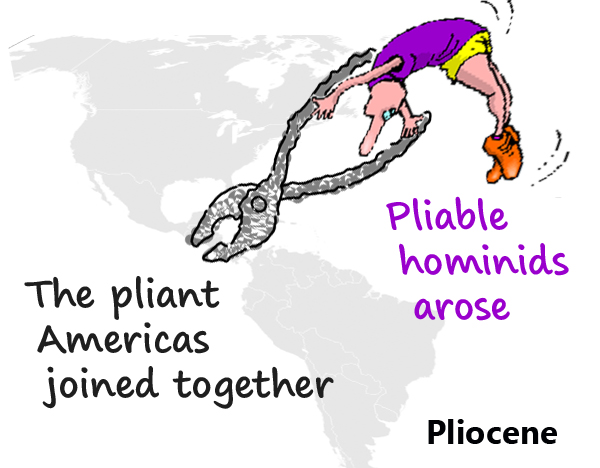

If you can visualize very limber (perhaps in distorted postures) ape-like humans, Pliable hominids might be satisfactory, or you may need to fall back on the pliers — perhaps an image of pliers bringing North and South America together.

If you can visualize very limber (perhaps in distorted postures) ape-like humans, Pliable hominids might be satisfactory, or you may need to fall back on the pliers — perhaps an image of pliers bringing North and South America together. Mild weather isn’t terribly imageable; you might like to imagine milk pouring from the joint where Africa and Eurasia have collided.

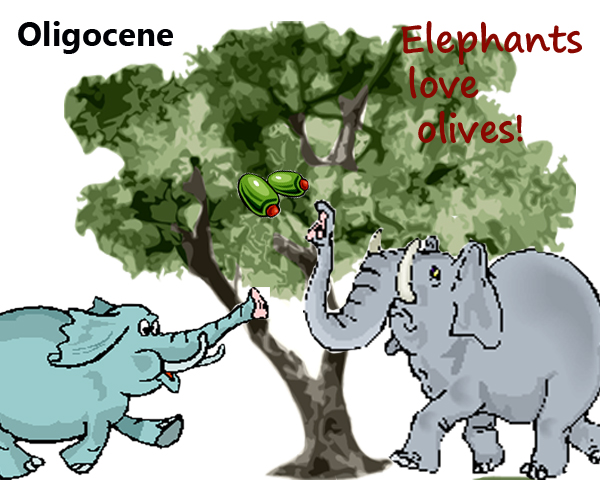

Mild weather isn’t terribly imageable; you might like to imagine milk pouring from the joint where Africa and Eurasia have collided. Oligarchs is likewise difficult, but you could visualize elephants under olive trees, eating the olives.

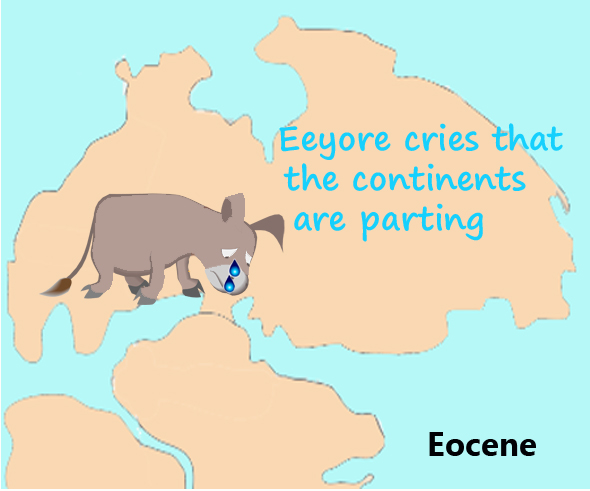

Oligarchs is likewise difficult, but you could visualize elephants under olive trees, eating the olives. And now of course, we come to the most difficult — the Eocene. Here’s a thought, for those brought up with Winnie the Pooh. If you have a clear picture of Eeyore, you could use him in this image. Perhaps Eeyore is standing on one part of the separating Laurasia (looking appropriately disconsolate).

And now of course, we come to the most difficult — the Eocene. Here’s a thought, for those brought up with Winnie the Pooh. If you have a clear picture of Eeyore, you could use him in this image. Perhaps Eeyore is standing on one part of the separating Laurasia (looking appropriately disconsolate).